What

is it that makes the objects and specimens of the medical museum so

compelling and repelling in equal quantity? What is it about the

malformations of the bottled monsters of the teratological specimen

that draws our horrified and delighted attention? Since the birth of

what is known in the west as modern medicine, the word

"monstrosities" has been used to describe physical

deformities, ‘irreducible to the "proper body" in their

singular, sometimes startling difference’ [1] These

accidents of nature suggest something other than the normal self, and

yet they are not outside our selves or nature, but recognisably part

of it. That sense of alteriety which gives such specimens their

fascination and appeal is tied to the uncanniness that is born of

strangeness within the familiar.

I

experienced this duality when, as a child, I arrived from an English

boarding school in Malaysia to find that everything I had learnt

about my 'mother country' was out of kilter. I thought that I was

English, but found that I was in fact alien, other, in a country I

considered home. Not only that, but I realised that the borders

between normality and the monstrous were rigorously delineated here

in a way which they had not been in Malaysia. There, in my Malay

mother's village, the lines between what was 'real', and normal, and

what was bizarre, uncanny, were much blurred. Monsters were all

around: in the jungle, or in the corner shop: everybody knew someone

who had too many fingers or toes – or someone whose uncle had been

eaten by a ghost, or an enormous snake. All these experiences were

equally valid. After trying to fit into the dull realism of Essex

life, I began, as an artist, to revisit some of these ideas of the

strangeness in familiarity, and at the same time began to explore the

confusion inherent in my own sense of who I was. Roy Porter suggests

that ‘our sense of self presupposes an understanding of our

bodies.' [2] There

had been a point, at school, when my interests were divided between

art and biology: so I began to work from my own fascination for the

body, and the medical collection.

My adult interest

in this material began after visiting Gunther Von Hagen’s' “Body

Worlds” exhibition in Brussels. It wasn’t, in the end, the

plastinated bodies that piqued my interest: rather it was a small

display at the end of the exhibition of pre-plastination preservation

techniques. In this darkened room there was a horrified fascination

as visitors clustered around the teratological specimens. This in

stark contrast to the rest of the exhibition where, by the end, most

people felt an ‘emotional anaesthesia’ [3] occasioned by yet another bizarrely posed body, become as bland as a

mannequin in some netherworld between science and art.

Yet his work

was inspired by the preparations of Honoré Fragonard (1732-99),

whose “Anatomised Cavalier” and dancing foetuses draw the gaze

where Von Hagen's preparations do not. Fragonard himself was

denounced as a madman for his pursuit of preservation. His ecorché

“Man with a Mandible”, with its rolling glass eyes, is both a

vision of a man horrified, and quite horrible in itself.

When I began my

research into the medical collection, there were two aesthetic

avenues of medical preparation that I was looking at: the wet

specimen, and the wax moulage. The use of the moulage came about to

serve the needs of dermatological diagnostics, as the wet preparation

did not preserve the colours of the skin well. More lifelike, the wax

allowed for casts made from living subjects, and gave a three

dimensional study which replaced the patient and did not decay.

Smaller models were often placed in glass jars like the ones used for

wet specimens – to further emphasise in the viewer a sense that

they were 'real'. Larger models warranted their own glass bier.

There

is a part-body in the Deutsches-Hygiene Museum

in Dresden of a woman giving

birth. It uses as its armature, disturbingly, the deceased woman’s

own pelvic bones. A number of disembodied surgical hands float above

the partially-dissected womb - all male, and neatly dressed at the

wrists with white cuffs and dark suit sleeves, hovering above the

anatomical Venus like cherubs around a Madonna.

These wax moulages

have a powerful effect, both when viewed individually and en masse:

the largest collection is at the Hospital of St. Louis in Paris, and

I defy anyone to remain unmoved by the ‘wall of syphilis’. All

these body parts are surreally segregated, removed from the whole so

that just the diseased part is on display, surrounded by a neat

border of fabric: mounted on a black board like a specimen, one is

not meant to imagine the whole, but focus on this intimate portion of

disease or deformity.

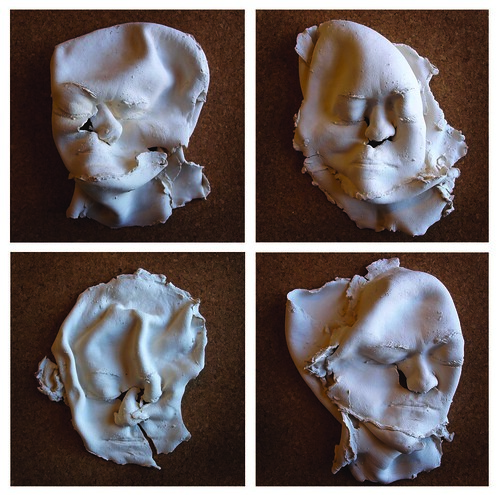

This

hyper-surreality of the moulage led me to experiment with casting my

own face. The fragility of the mould resulted in my not being able to

take many casts from it: however as the mould broke up, the casts

began to resemble the deformities of the moulage – in this process

I felt that I was taking the life mask through processes that

referenced the effects of congenital accident or deformity, removing

it from the body, taking it as part-feature, metonomous. I kept the

casts of my slowly collapsing face colourless, and mounted them on

coloured boards instead.

They made me

reconsider myself in terms of that childhood experience of finding

that I was an alien as much because of my skin colour as my

post-colonial upbringing. How strange to be other in the country one

thinks of as home: and an equally curious sensation, to see your own

face disembodied. At this point I began to look again at the wet

specimen, and specifically examples of heads and faces.

Wet specimens are

body parts or a whole foetus preserved in fluid such as formalin or

alcohol. They have been described as ‘objects between nature and

representation, art and science’[4] The effect of seeing these aberrations, further distorted by the

curve of the preserving jar, is truly uncanny. Freud, in his essay on

the subject, recalls an occasion where he comes face to face with his

own reflection in a train door, and momentarily mistakes it for

someone else: not only that, but someone that he found unpleasant to

look upon. This sense of something at once sinister but homely echoes

in the correlation of preservation in jars; of bodies, or of fruit.

This is particularly true of the teratological specimen. Here, the

preserving jar acts as a pseudo-womb, the little monsters within

floating placidly in the urine-coloured liquid as if awaiting the

moment of birth.

Actually,

this, while a poetic image, is not true: often the expression on

their faces (if they have one) is anything but placid, and the

illusion of the amnion is altogether ruined by the evidence of

autopsy: the lack of a brain, large stitches across their heads,

glass rods keeping them in position. In the case of the specimen

known as 'sirenome' in the Musée Fragonard, the foetus is held in

position by a cord tied, disturbingly, around its neck.

I

had this idea of toying with the purpose of the wet collection,

namely that it should preserve – I wanted to make work in which the

heads, in their different materials, decayed, changed and altered in

the sterile confinement of their container. The artist Marc Quinn

made his head out of his own blood, perhaps the ultimate act of

self-portraiture: I thought about using materials such as

clay, wax, bread, shit, or fat, and then immersing the heads in

liquids such as milk, urine, wine - even kombucha, a living liquid.

Here I wanted to reverse the notion of the liquid in the jars acting

as a preservative, and reference the familiarity of foodstuffs in the

un-homelike environs of the laboratory. In order to do this properly,

however, I first had to cast my own head.

Much

of what we are, as humans, is determined by our appearance, and much

of that, as a woman, is determined by hair. In order to truly face my

Self, I realised that I had make my head naked. And so I shaved my

head, and made my first uncomfortable discovery– that the back of

my head was quite flat. This first head-casting was a two-part mould

that involved the use of dental alginate, a pink rubbery substance

that smelled, bizarrely, of mint. The alginate broke apart while

being removed from my face and I managed to get only one cast from

this distorted mould. Interestingly, having been researching life and

death masks, this cast brought to mind a particularly famous death

mask – that of L'inconnue de la Seine.

At this point I

decided to revisit my visual research in the museum.

Interest in the

medical collection, particularly for teratological specimens,

straddles a line between science and sideshow. Early collections by

surgeons later opened to public, and these displays further blurred

borders between the gallery and the teaching museum. During my visits

to the Hunterian and Wellcome in London, and the Dupuytren and

Fragonard in Paris, I began to wonder - who is going to these

collections? Not scientists any longer, but the curious and creative

autodidact. The Mütter Museum, a noted medical museum in

Philadelphia, has daily visits from eager schoolchildren and their

teachers rather than medical professionals.

In the Dupuytren,

the only cabinet with lights is the teratological cabinet, where the

double-headed kitten and goat nestle in jars side by side with the

thoracopagus foetuses and other monstrosities. Each small corpse

exhibits alongside its deformation a particular and individual

appearance: their little faces angry, or vacant, indifferent. The

Dupuytren also has two faces half eaten by cancers: part of their

compulsion comes from the obvious and horrible disease, but part –

for me at least – from the unique and recognisable humanity of each

face: one with soft, receding hair floating silkily in the preserving

fluid: one with dark brows and beard, and an arrogant twist to his

lips.

In the Dupuytren,

the only cabinet with lights is the teratological cabinet, where the

double-headed kitten and goat nestle in jars side by side with the

thoracopagus foetuses and other monstrosities. Each small corpse

exhibits alongside its deformation a particular and individual

appearance: their little faces angry, or vacant, indifferent. The

Dupuytren also has two faces half eaten by cancers: part of their

compulsion comes from the obvious and horrible disease, but part –

for me at least – from the unique and recognisable humanity of each

face: one with soft, receding hair floating silkily in the preserving

fluid: one with dark brows and beard, and an arrogant twist to his

lips.

Peter the Great

(1672-1725) was famously the possessor of a notable wunderkammer- after a visit to Leiden, he bought the entirety of Frederik Ruysch's collection of anatomical preparations. His

mania for specimens, among other drives, led him to execute his

wife's lover, whose head was then preserved it in a jar; though in

the interests of fairness, he did the same to his own lover. These

bottled heads were later found by his grandson's wife, who remarked

upon their youthful appearance before, sadly, having them buried.

There

is a particularly macabre head in the Mütter Museum. It is not on

general display, but is down in the cold storage of the wet room, in

a jar held upright by a simple metal bookend. It is Negroid, and for

some reason the eye has been rather brutally removed. It is cut in

half, right through the delicate, pouting lips and weak chin;

however, the particular horror and humanity that I found in this

specimen was, for me, evinced by the collection of white-headed

pimples on the colourless, sallow cheek.

Armed with a

visual cortex full of bottled horrors, I returned to the workshop

determined to try again. This time, another colleague was finally

intrigued enough by my bald head to make a three part mould, starting

with the back of my head, then my chin and neck, and finally – nose

straws and earplugs in place – my face. Word had travelled around

the college, in light of my earlier attempt, and this casting was

observed by a large group of fine art students, all happily making

notes and taking photographs of my shiny Vaselined pate. I

experienced on this occasion something strange: people were talking

to me throughout this process, up until the point at which my face

disappeared under the plaster. Suddenly, they ceased talking to

me, and began to talk about

me, like an object. I lay there, offered up for display like a

medical Venus, listening to the chatter around me, as if I were

suffering from 'locked-in' syndrome – for the first time I had the

experience of moving from person to specimen.

Apart from a brief

moment of fear when the mould was momentarily stuck to my ears, this

was a successful mould-making. The first cast I took from this mould

was made using expanded latex, which resulted in a rubbery squashy

head that I delighted in carrying around like a baby. The happily

uncanny experience of coming face to face with my own face resulted

in a number of inappropriate behaviours, such as sticking it up my

jumper so the features protruded like an alien baby about to explode

from my belly.

Perhaps the Alien

analogy is close to the effect I was experiencing: in the film Alien

Resurrection, when Ripley enters the room full of rejected or

malformed mutants in huge jars, she sees herself, repeated; the

monstrous mother worse than the alien mother of earlier films in the

horror of their sympathetic humanity. They are her, but they are not:

they are further deformed by their failure to live up to their true

monstrosity: she is ‘haunted by (these) alternative versions’ of

herself. [5]

Perhaps the Alien

analogy is close to the effect I was experiencing: in the film Alien

Resurrection, when Ripley enters the room full of rejected or

malformed mutants in huge jars, she sees herself, repeated; the

monstrous mother worse than the alien mother of earlier films in the

horror of their sympathetic humanity. They are her, but they are not:

they are further deformed by their failure to live up to their true

monstrosity: she is ‘haunted by (these) alternative versions’ of

herself. [5]

What

interested me in my playing with the latex head was not only my

reaction to my double, but others in seeing me with my doppelgänger.

Everyone felt that seeing me, for example, kiss my own rubbery head,

was wrong and repulsive in ways that they couldn't articulate. This

is where I felt I began to tap into those primal reactions that were

evoked by the bottled babies, through a reinterpretation of both the

aesthetics of the teratological wet specimen and the facial cast or

moulage.

Eventually

I made a master mould which allowed for casting in a variety of

materials. Having been earlier inspired by the plaster life and death

masks in the Galton collection, I began to make a series of casts in

plaster. By now, I was less interested in making the heads out of the

abject materials that I had started with, after observing the

uniformity of the plaster. The blank whiteness of it in contrast to

my own skin was so 'other' in its lack of colour and featurelessness.

So taken was I by the rows of blank white plaster heads that

it seemed to me that the heads themselves

should remain inert, white and anodyne as aspirin: it was the liquid

that they were immersed in that should reference this contrast

between purity and abjection.

There

was also something of a compulsion about repetition, similar to what

I found when making multiples of my eyes or lips. The decapitation

seemed peculiarly uncanny. Having commissioned a number of

jars that were watertight and large enough to contain my head, I

built a cabinet to put them in – with lights – and proceeded to

fill each jar up to the nose with fluids – milk, wine, water and

urine.

The cabinet took on

a religious aspect as the fluids reflected the light like

stained-glass, and seemed to create a space somewhere between museum

and gallery, clinic and altar. The fluids themselves took on

religious and transformative significances: the blood of Christ, the

milk offered to Ganesh, the psychotropic reindeer urine imbibed by

the shamen of Lapland. The jar containing water remained empty of a

head, as I eventually determined this should be the 'control' jar. It

was later remarked to me that the empty jar was more disturbing than

the jars with heads in, as the absence seemed frighteningly more

uncanny by dint of its inexplicability – one could envisage, it

seemed, a head in a container that is head-sized, but the lack of

head seemed to raise a deep feeling of unease.

In

the end, the casting of my head did not result in work that was

compelling in the way that the teratological specimens or moulages

were: to my mind they evoked a different kind of horror: the

juxtaposition of clean white plaster and rotting, foul liquids had

the appearance of some sordid experiment gone awry. The work became

instead a visual exploration of the way in which the museum specimen

seems to reflect, in some measure, residues of the human: return the

gaze of the spectator to create a deeper reflection, from object to

abject, self to other, and back. Here, in the rows of heads colouring

and dissolving in unnamed liquids, the artist becomes both subject

and object.

All this serves, I

hope, to connect the contemporary concerns of science with an

unconscious atavism - a simultaneity of the pure

and the profane, the proper and the monstrous. But to my mind I have

only just begun the first step in a body of work which was inspired,

originally, by a single desire: to put my own head in a jar.

1: Jeffrey Longacre, Review of Monstrosities: Bodies and

British Romanticism, by

Paul Youngquist. College Literature, 22 September

2005, University of Tulsa.

2: Roy Porter, Flesh

in the age of Reason

London: Penguin, 2004:44

3: Taken

from the chapter 'The limits of empathy' in Linke, Uli “Touching

the

Corpse:

the unmaking of memory in the body museum” in

Anthropology Today

Vol.21

No.5, October 2005: 13-19

4: Taken

from information sheet about the AHRC Research Network "The

Culture

of Preservation", a series of workshops and

lectures at UCL run by Petra Lange-

Berndt and Mechthild Fend, London May/June 2011.

5: From

part 3 of Zizek, Slavoj

The Perverts

Guide to the Cinema filmed

by Fiennes,

Sophie. Lone Star Films, 2006

Images:

1 'Man with a Mandible, Musée Fragonard, Paris

2 'moulage' clay and wood, Lisa Temple-Cox

3 'Sironeme', drawn from specimen in Musée Fragonard, Lisa Temple-Cox

4 face cast and death mask of L'inconnu de la Seine

5 face, drawn from specimen in Musée Dupuytren, Lisa Temple-Cox

6 'face baby'

7 'Cabinet', assemblage/installation, Lisa Temple-Cox

selected bibliograpy:

Alberti,

Samuel J.M.M. Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth

Century Britain Oxford:OUP 2011

Asma,

Stephen T.

Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: the Culture and Evolution of

Natural History Museums Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2001

Daston,

Lorraine and Park, Katherine Wonders

and the Order of Nature 1150-1750

New York: Zone Books 2001

Daukes,

S. H. The

Medical Museum London:

The Wellcome Foundation, 1929

Foucault,

Michel The Birth

of the Clinic London:

Routledge, 1997

Freud,

Sigmund “The

uncanny”(1919)

in Art and

Literature London:

Penguin, 1990

Knoppers,

Laura L. and Landes, Joan B. (eds)

Monstrous Bodies/political monstrosities in early modern Europe

Ithaca/London:

Cornell University Press, 2004

Kristeva,

Julia Powers of

Horror: an essay on abjection New

York: Columbia University Press, 1982

Linke,

Uli “Touching the Corpse: the unmaking of memory in the body

museum” in

Anthropology Today Vol.21

No.5, October 2005: 13-19

Porter,

Roy Flesh in the

age of Reason London:

Penguin, 2004

Sawday,

Jonathan The

Body Emblazoned London:

Routledge, 1996

Schnalke,

Thomas (Author) Spatschek, Kathy (Translator)

Diseases in Wax: The History of the Medical Moulage Quintessence

1995

Zizek,

Slavoj The

Perverts Guide to the Cinema filmed

by Fiennes, Sophie. Lone

Star Films, 2006