“The clinic was … the first attempt to order a science on the exercise and decisions of the gaze” - Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic

There is an ‘order of things’ within the conceptual architecture of a space that exists, in potentia, in both clinic and altar. What is the relationship between these systems? Both have relevance to our exploration of self, during which we invariably encounter something primal, unconscious, alongside the scientific - here represented by the supposedly objective medical gaze.

We use art in our search for self, and art uses media that not only signify the body – flesh, blood, faeces - but invoke a sense of the abject: a separation of subject from object, a rejection of death. The aesthetic of the medical museum and its exhibits may have similar psychological effects on its visitors, containing specimens that simultaneously attract and repulse. This phobia or horror that, at the same time, exerts a kind of cathartic pleasure in its experience, may cause the viewer to reflect on the materiality of their own body.

Is this art that is merely a “materialist interpretation, infantile celebration of bodily fluids”?[1] Can the philosophy of abjection be applied to the anatomical specimen? Interest in this material “swings like a pendulum between the gutter of morbid fascination and the ponderings of “pure” knowledge.”[2]. The gaze of the viewer within the transformed gallery moves in the same way between science and religion, losing the ability that supposedly defines modern man: to separate and distinguish between these states.

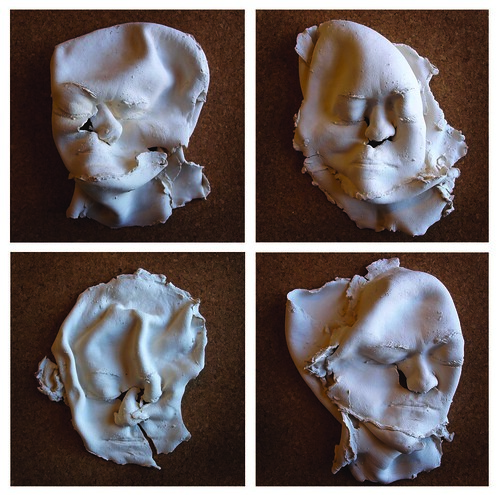

In The Medical Museum, S.H. Daukes states that the eye must take first place: it is “the main avenue for diagnostic information”. Martin Jay notes that, “there can be few human interactions as subtle as the dialectic of the mutual gaze.”[3] In the casting of the face, however, the eyes of necessity remain closed, thus blurring the distinction between life mask and death mask, in much the same way that the preserving fluid and curve of the glass jar further distorts the teratological specimen. We submit ourselves to this medical gaze, reclassified by order of anatomo-clinical perception.

Our relationship with our bodies and selves is reflected in the mirror of the operating theatre. The theatre of medicine becomes the stage, the screen: the speculum becomes spectacle, the looking-glass of self turned outward. This narcissistic obsession with faciality may be a denigration of the knowledge of our mortality - or it may be an attempt to realise it materially.

The work shown is a visual exploration not only of the way in which the museum specimen can seem to reflect, in some measure, residues of the human, but return the gaze of the spectator to create a deeper reflection of self: from object to abject, self to other, and back. Here, the artist becomes both subject and object. Here are faces and eyes, made diseased and necrotic by the rough textures of the materials; rows of heads colouring and dissolving in unnamed liquids. All these serve to connect the contemporary concerns of science with an unconscious atavism - a simultaneity of the pure and the profane.

[1] Benjamin Buchloch The Politics of the Signifier II: A Conversation on the "Informe" and the Abject October, Vol. 67 (Winter, 1994)

[2] Stephen T. Asma Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: the culture and evolution of natural history museums (2001) Oxford University Press

[3] Martin Jay Downcast eyes: the denigration of vision in 20C French thought (1994) University of California Press.

[4] Alphonso Lingis Chichicastenango in Carolyn Gill (ed) Bataille: writing the sacred (1995) Routledge London

No comments:

Post a Comment